I have never been a fan of the whole “sharing economy” idea. For the most part, people have a hard time taking care of the things that they actually do own, much less something you can pick up on the street and leave wherever and whenever you wish. We have all seen the pictures of “shared” bikes being left up in trees, on top of telephone poles, or simply dismantled and left in pieces while the good parts are all salvaged. And yet, the number of companies entering the space proliferates.

Bird Global Inc. (BRDS) offers battery-powered bikes and scooters for the sharing economy, with a bit of direct-to-consumer product sales thrown in. Back in 2018, about a year after its founding, BRDS made headlines by becoming the fastest unicorn to reach the $1 Billion valuation landmark, likely on the back of its entrepreneurial founder and his prior history of startups and quick exits.

Problems from the get-go. The company is headquartered in Santa Monica, a city has been dealing with an influx of scooters for the past few years, and therein lies one of the problems. http://www.santamonicanext.org/2018/01/bird-scooters-public-nuisance-or-the-future-of-transit/ According to this story from 2018, Bird and its founder were sued by the notoriously progressive city of Santa Monica for “operating a business without a license or vending permit, and leaving the scooters unattended on public property.” I guess suddenly dropping hundreds of scooters out on the public streets wasn’t the best way of introducing yourself to your future “partner.” As positive proof that something like Karma does exist, earlier this year BRDS was not selected to participate in the city’s pilot micromobility program even though they placed fourth out of eight applicants and the city was supposed to accept the top four applicants; their scooters have since been removed from the city’s streets. https://dot.la/bird-app-santa-monica-ca-2653017433.html Among the reasons why? “Santa Monica transportation staff made their selection based on 10 different criteria. Bird was dinged for affordability, customer service, durability, safety and maintenance/ operations.” This all comes, of course, on the back of a rocky COVID-driven 2020 which saw Bird fire more than half their staff and unload their ritzy Santa Monica HQ even as investment giant Fidelity market down the value of their BRDS holdings. https://dot.la/bird-scooter-2648232688.html But that’s all in the past, right?

Rainbows and Unicorns. Going from billion dollar unicorn in which some big names lined up for a slice to a quickie reverse-merge-into-a-SPAC that had a pretty paltry 16M share PIPE offering which is now underwater must be a tad humbling, especially for a crew used to a more fawning reception. The news accounts all said that they were coming out with a $2.3B market cap https://techcrunch.com/2021/05/12/bird-rides-to-go-public-via-spac-at-an-implied-value-of-2-3b/, but that seems to be based on 239M shares outstanding at the time, while the most recent prospectus notes that there are 289M+ shares of class A common stock out there (the CEO has 34M shares of super-voting stock (he has around 75% voting rights for his 13% stake) and there are 30M earnout shares that pretty much always seem to get earned out, and 77M incentive shares that automatically get cranked up each year). Even at $8, which makes the $10 PIPE placement a tad underwater, this thing has a market cap substantially higher than what was reported.

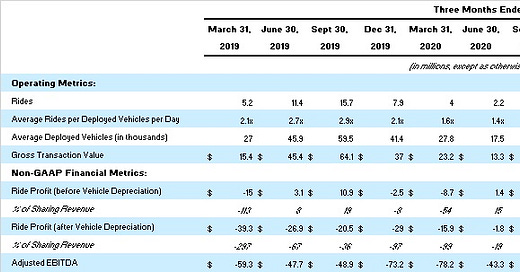

Stalled Revenues? From a revenue standpoint, and I’m willing to give them the benefit of the doubt here, you can’t really count 2020 for something like BRDS. After all, their business model makes the most sense in densely populated urban centers or perhaps heavily frequented vacation destinations, both of which were most heavily affected by the lockdowns. So I’m willing to give them a pass for 2020, but comparing 2019 to 2021 is another matter. The top line in the chart below shows trailing revenues and, as you can see, they are up only slightly more than they were back in 2019.

Seasonality and Traffic Patterns. It’s also a highly seasonal business, making the most sense when the weather is warm and the skies are clear; rain, snow, and cold hardly make for ideal biking or scootering conditions. Finally, their business model also tends to work best in places that have a high amount of foot traffic with inadequate parking situations such that leaving your car behind and renting a scooter makes much more sense than dealing with parking lots and congested streets. In order to encourage alternative transportation methods, the city of Santa Monica, where I happen to have grown up, has removed many traffic lanes (where there used to be 2, now there is only 1) along busy streets and designated those areas for scooters or bikes. One unintended consequence of this, of course, is that more traffic moves into residential neighborhoods which is less desirable but something the city planners are willing to live with.

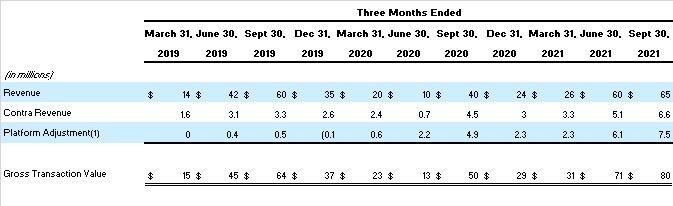

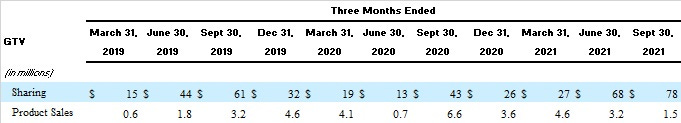

Gross is Better. Now, you’ll notice from that first chart the term “GTV” which stands for “Gross Transaction Value.” GTV adds back any retail discounts or refunds given to platform partners or retail customers or other purchasers of its products. These are labeled as “contra revenue” and “platform adjustments.” If I wanted to start a little business in my community that would rent BYDS scooters and bikes out to the vacationing masses, BYDS would sell me the scooters at cost (according to their web site at least) while taking a piece of the rental fee each time the scooter or bike found a rider. These discounts all get added back to the GTV calculation, which the company believes is a better indicator of the success and penetration of their business model than just revenues alone. In the following table, they break down GTV a bit further into their “sharing” and “product sales” buckets, and “sharing” clearly makes up the majority of their top line.

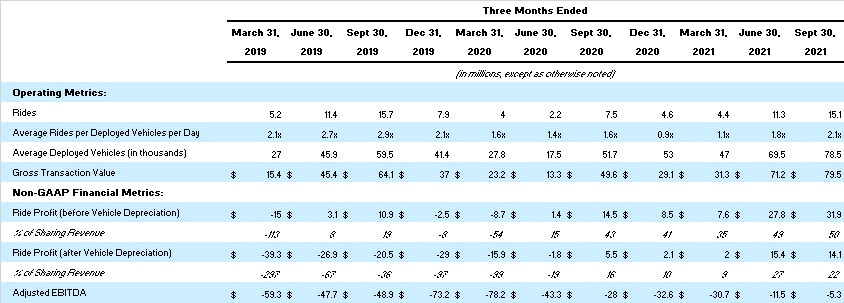

Rides down, Vehicles up. The company uses a few other operating metrics that they believe best symbolizes their company and will help investors track their progress. These include “Rides” and “Deployed Vehicles;” Deployed Vehicles are only the number of vehicles available to share and does not include broken, stolen, out-of-service, or removed-from-service vehicles; Rides is the number of trips completed by their sharing customers; Rides per Deployed Vehicle is simple division.

The first thing to note is that the number of rides in Q3 2021 has not yet achieved the same level as that of Q3 2019. That despite the fact that the number of deployed vehicles rose dramatically from 59.5K to 78.5K (while they were forced to contract in their home city of Santa Monica they are expanding in other markets), which brought down the average number of rides per deployed vehicle. Given that many urban centers have yet to return to pre-COVD traffic patterns, and the level of attrition and staff cutbacks, this strategy of trying to expand in the face of adversity may be a bit premature.

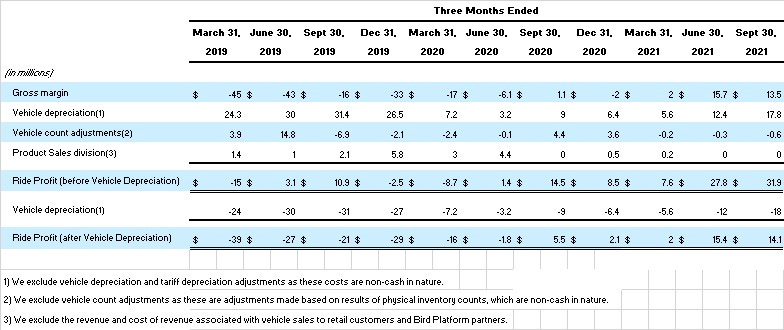

A Prophet in a Profitless World. Yet, even though there are fewer rides being completed and a higher number of vehicles available for riders to use, somehow the “Ride Profit” managed to triple while “adjusted EBITDA” continues to trail. The following chart is a reconciliation of gross margin to their ride profit calculation, with an explanation at the bottom that says basically everything they are adding back is “non-cash” in nature.

Depressing Depreciation. The depreciation calculation is kind of interesting. According to their prospectus, they “depreciate released vehicles using a usage-based depreciation methodology based on the number of rides taken by customers.” So in a way, when customers are using their scooters less and taking fewer rides, it leads to lower levels of depreciation across their entire fleet, which can make their results look better than they actually may be. Another interesting fact about depreciation is that it appears to be extended with each new model release of their Bird vehicles: BirdZero had a half-life of 12 months, while the most recent BirdThree is up to 24 months. I’m sure battery technology has evolved a bit in the 3 years in between, but a double seems like a bit of a stretch.

Losing Traction. One of the more puzzling parts of the BRDS business isn’t necessarily their “sharing” revenues, but rather the lack of traction among their retail products. As shown in that second chart, product sales are down over 50% in the past couple of quarters compared to the same period last year (which was the COVID year) and are at a low for the year despite being a seasonally strong quarter. They are also lower than the same period in 2019 even though their product catalog has expanded dramatically. For kids, they launched a non-electric scooter called the “Birdie” in late 2019 (like a Razer scooter but more expensive). The “Bird Bike” is $2,299 and takes its place among dozens of different manufacturers, many of which have been around for years and have a distribution and retail network already in existence. Likewise, the “Bird Air” scooter has limited range but is much lighter and at $599 less expensive than their fully-featured BirdOne coming in at $1,299. I think a problem the company is going to run into is they are pricing their products at a premium price level and they basically have zero brand recognition, unlike a Razer or Trek or even Huffy. Their styling is practical but bland, and many less-expensive no-name manufacturers also have integrated batteries into their frame designs using up to 1,000 watt motors vs. the 500 watt motors utilized by Bird. Bird says that their bikes have a 50 mile range, but it’s really only 20 miles without the rider assisting (a fairly rare site). The specs for the Bird Bike also suggest a minimum rider height of 5’8”, which is sadly above 50% of the total population and probably close to 90% above the kid or female population and a similarly high number for various demographics. So underpowered, lesser range, bland styling, zero name recognition, premium pricing, limited dealer network, and few color options may make for a pretty limited market and a rather tough sell. I ride daily along the coast down here and have to say 75% or so of the bikes going down the bike path are now electric. I would say around half have the aggressive big, fat, knobby tires one finds on the recent fat tire mountain bikes, but without the standard mountain bike look, which is not something that Bird is currently offering.

Revenue Opportunity. And how about those “statistics” that are meant to whet the investor’s appetite, but do nothing more than increase doubt in the eyes of some? The company’s presentation says that they have an $800 BILLION YEARLY revenue opportunity. Yearly. Billion. Really? According to them, of the 8 trillion trips taken globally each year, 5 trillion of which are less than 5 miles in distance, of which they believe 900 billion are done by addressable users, and if they can just capture 200 billion of those globally, then that translates into an $800 billion yearly revenue opportunity. Just think of how many scooters that would be, too. 200B annual trips is 550M daily trips which is around 250M scooters!

GHG Savings? Their presentation also features a chart that shows only 51% of alternatives to Bird Rides have higher emissions, though each Bird scooter supposedly offsets greenhouse gas emissions by the equivalent of 40 trees. So if 49% of the alternatives to Bird Rides produce zero CO2 (walking, biking, personal scooter) then how exactly does an electric scooter save any trees on those? One chart you will likely never find is the one that spells out the health detriments to an electric bike or scooter compared to the 49% ordinary walking, biking, or scootering, it is most likely to replace, like the cardio exercise you receive from physical activity or the number of accidents that happen. As I mentioned earlier, bike paths around me are now littered with electric bikes usually at the expense of ordinary bikes; it’s not that there are now more vehicles on the bike path, but rather there has been a transition to electric from non-electric for the majority of the users.

Bird’s hopes don’t appear to lie in the retail channel; there are way too many better established brands and manufacturers who were there long before Bird came along and they have many additional interesting style and design choices. Can they always come out with more styles to match what other manufacturers are doing? Of course, but building a premium brand without any unique features will be both incredibly difficult and expensive. Should they choose to slug it out on the retail front, they will need to match the competition and dramatically ramp up their marketing and R&D spend. Their hopes would appear to lie more in the sharing economy, where they are in competition against Lyft and a myriad of other names and manufacturers https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/e-bike-sharing-market-size-2021-size-shares-top-region-industry-outlook-driving-factors-by-manufacturers-growth-and-forecast-2026-with-top-growth-companies-2021-11-02 in all phases of development, but which is likely not as brutally competitive as a retail approach. The company believes that a “first mover advantage” exists for them, even after they were booted out of their very first market. Perhaps the company’s rise to billion dollar unicorn was a bit hasty, and their subsequent SPAC offering more a sign of desperation than strength.